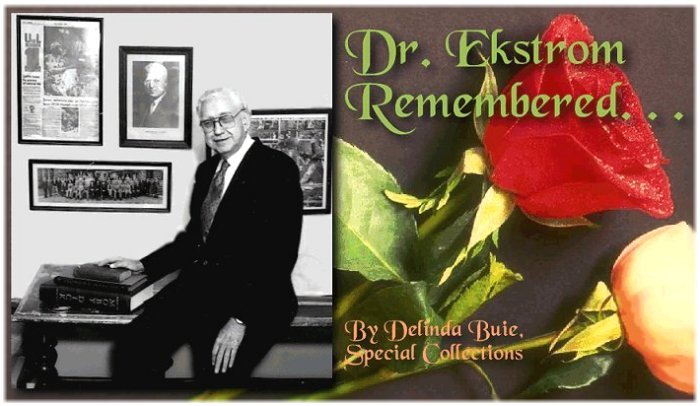

When Dr. William F. Ekstrom walked in wearing a golf shirt and glowing after a brisk walk from his home in Treyton Oak Towers, it was fun to introduce him to students and watch him watch their faces as they gradually connected the avuncular man before them with the name on the front of building. He was proud of the Ekstrom Library, proud of all of us who work here, and intensely interested in the role we play in the education of students. He came often. Although he had long ago given us almost all his books, sometimes he brought a present. One day he brought a rare Wordsworth edition given him by Dr. Mary Burton who had been his colleague in the English Department. He spoke of her with admiration and affection, then asked that the bookplate mention her alone. Several years earlier, just before her death, I had visited Dr. Burton and listened as she spoke of him with that same admiration and affection. She credited much of her recognition as a Wordsworth scholar to Dr. Ekstrom's interest and unwavering support. "He treated the women faculty as equals long before any other man did."

Sometimes he came bringing friends to enjoy one of our most beautiful fine press books, the Arion Press edition of Moby Dick, given to the Rare Books Collection by colleagues in the English Department in honor of his retirement. At first he was wary of the presentation of his beloved Melville in a "pretty book," but he came to love this impressive volume, especially the Barry Mosher woodcut of a great sea wave curling into the initial letter of "Call me Ishmael…" and sweeping the reader into the text. After his retirement he established an endowment so that we could buy more Melville, including rare first editions, and other American texts: Fitzgerald and Faulkner, little magazines and papers of emerging authors. He gave moral support and practical advice to his former colleagues in English, but he wanted his financial gifts spent on materials students could use.

Occasionally over lunch or coffee he would tell stories. He told of a student about to graduate and thinking of a career in teaching. The young man came to him asking the necessary requirements; Dr. Ekstrom responded in his usual fulsome manner, closing with his opinion that the most important attributes of a teacher were a love and devotion to a particular subject, a deep regard for students, and a passion for connecting the two. Dr. Ekstrom laughed as he remembered how the young man departed in disappointment because although he loved literature, "he found his fellow students rather boring." Dr. Ekstrom never found students, or anyone else, boring. He was keenly aware of privileges in his upbringing and career and wanted to extend the gifts given him to others.

After Dr. Ekstrom left the English Department to become UofL's first Academic Vice President, he had given up teaching. After his retirement many of us felt it would be a fine thing if he gave a series of lectures on Melville. He was tempted, but with characteristic integrity declined. He explained that he had not done any original research during the years he spent in Grawemeyer Hall and felt that was a necessary part of effective teaching. Instead he turned his retirement to supporting the work of younger colleagues, working as a senior member of the Library Associates and major donor to the Libraries, and offering his knowledge of community in Louisville, government in Frankfort, and history of the University to Presidents Swain and Shumaker.

Perhaps his greatest satisfaction in his retirement was the work he did to improve the lives of young people outside the university. He served on the board of Buckhorn, a home for abandoned and abused young people in Eastern Kentucky. Since Dr. Ekstrom never just 'served on the board,' he made regular trips across the mountains to spend time with the children. Once when we were to meet for lunch he called and awkwardly asked for a ride. He was temporarily without a car, his having given out halfway up a mountain road and remaining impervious to the ministrations of local mechanics. As he told the story I had a vivid mental picture of Dr. Ekstrom in shirtsleeves, standing in mud, miles from a telephone, peering at the smoking remains of his engine. Later he became a sort of godfather at large to the Day Spring, Inc. community for mentally retarded adults, many of whom joined the procession at Dr. Ekstrom's memorial service.

Dr. Ekstrom once reflected ruefully that a former colleague, intending a compliment, had commented that "he always sensed a rise in the level of tranquility whenever I stepped on the campus." He laughed that the Courier Journal referred to him as a "workhorse" and opined the epithet was due to what he called his "lack of leadership pizzazz." "Pizzazz" admittedly is not a word particularly descriptive of Dr. Ekstrom, but anyone who knew him even slightly will remember his dignity, good humor, and radiant interest in people. As an administrator he was an effective leader who steered the University of Louisville through civil unrest, sit-ins and even sewer explosions. He helped navigate us into the state system of higher education and toward a more diverse curriculum. As a Swedish bachelor professor Dr. Ekstrom taught American and English literature. Far more importantly, he lived out and modeled ideals of integrity and compassion as he nurtured generations of students.